Originally posted by Megan

View Post

Announcement

Collapse

No announcement yet.

What are you reading now?

Collapse

X

-

I'm not sure which is best, I have a translation by Louise and Aylmer Maude which I read about 10 years ago. I also have the Sergei Bondarchuk film which is excellent particularly for the battle scenes - I think it was the most expensive Soviet film made and quite amazing for the time. Andrew Davies (he of 'Pride and Prejudice' and 'Middlemarch') is adapting 'War and Peace' for tv and I think it's due for release next year.'Man know thyself'

-

Thanks Peter,

The older translations have never lost their value and have a charm all of their own.

The set pieces are particularly good, but translation is like anything else and it moves on in the same way that culture does. There are different ways of translating a text. Umberto Eco, has some of the most profound things to say about how we go about translating a text. Basically, he says when you have a foreign language and want to translate it into your own. There are really only two ways of doing it. One is to modernize the text, that is to make sure the meaning is accessable to modern readers. The other way is to archaize, and that means to try to preserve the idiom of the time in order to try to attempt to get as close as possible to understanding the text in the way the original readers did. This is not such a big thing with Tolstoy because it's only one hundred or so years old. But it becomes a real issue with classical languages, which are effectively dead. That said, it is a bit of an issue with war and peace, because Tolstoy is writing about a period one hundred years before himself, and so it is something that a good translator has got to give a lot of thought to.

I have heard of bad translations of Tolstoy where they almost comically try to anglicize converstions and sound like cockneys speaking hundred years ago. This would even have been wrong.

Thanks for the info about the forthcoming film or War & Peace, I shall look forward to that. ‘Roses do not bloom hurriedly; for beauty, like any masterpiece, takes time to blossom.’

‘Roses do not bloom hurriedly; for beauty, like any masterpiece, takes time to blossom.’

Comment

-

Interesting Megan - the idea of modernising is slightly worrying when you consider the average number of words in use is shrinking and also the lingo of the internet - inevitably much is lost or even distorted. When Tolstoy wrote 'War and Peace' the historical events were within living memory at just over 50 years, not a century and he undertook a great deal of research.'Man know thyself'

Comment

-

I once saw a Russian film version of War and Peace which I liked very much, but it cannot be Bondarchuk's one for it was released in the 1970's. Wikipedia has a huge article on Bondarchuk's picture which is interesting reading material.Originally posted by Peter View PostI'm not sure which is best, I have a translation by Louise and Aylmer Maude which I read about 10 years ago. I also have the Sergei Bondarchuk film which is excellent particularly for the battle scenes - I think it was the most expensive Soviet film made and quite amazing for the time. Andrew Davies (he of 'Pride and Prejudice' and 'Middlemarch') is adapting 'War and Peace' for tv and I think it's due for release next year.

Comment

-

The book I most recently read, or rather reread, with the greatest relevance to this community is Roland Gelatt's "The Fabulous Phonograph, 1877-1977", published the year its narrative ends. It's an interesting, enjoyable read, and to my delight classical music centric for much of its length.

Since then I completed a book lent me by my brother, the autobiography of a "pro" wrestler. Now, I'm not much in to either pro wrestling or celebrity. But such books can provide harmless entertainment, as this one did. In any case, it gives me something to talk about with my brother, who has no use for classical music.

Prior to the Gelatt, I attempted the third volume in a recently published continuation of one of my favorite fantasy series. The author's two earlier trilogies centered on this same character are what initially turned me on to the fantasy genre during the mid 1980s. I've read those early trilogies eight times. After the second trilogy, the author took a break of over twenty years before returning to the subject. I've found the new books a great disappointment. I struggled through volume one, took several attempts and maybe four years to finish volume two, and threw in the towel on volume three (of four) after over one-hundred pages. In fact I bought volume three only because I found it used in hardback dirt cheap. I do, however, hope to finish it at some point.

Having just finished the wrestler autobiography, I'm not sure what to tackle next. I'm leaning toward a book purchased just recently at Barnes and Noble, "The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason" by Charles Freeman.Last edited by Decrepit Poster; 12-09-2014, 11:54 AM.

Comment

-

Hi DP. I am a great of Closing of the Western Mind.

I wrote the following article a while ago for a magazine.

Hope you find it interesting.

In the tide and course of human affairs, at epiphany-like moments, rare books appear that shine a light so dazzling on the falsehoods on which our modern world is founded that we are momentarily blinded. The late Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind was, is, such a book. To this reviewer it is, with the Warren Commission Report, the most important document to appear in the last 50 years. It was published in 1987 but, even today, it’s unclear whether we have the book, whose importance has only increased over the years, entirely in focus. Its appearance was a defining moment in our collapsing culture. It was hailed by what might be called all true libertarians as THE book of the times, a mighty, coruscating attack on the aetiology and epidemiology of cultural Marxism. The comparison with the Warren Commission is not fanciful. That report, of course, chronicled, in oceanic depth, the Marxist pathways and pathology of one Lee Harvey Oswald whose cry “I’m just a patsy!” (endlessly misinterpreted) accurately codes for “I’m just a patsy of the capitalist system!” The ‘liberal’ Left, predictably, came not to praise Bloom, but to bury him, employing every abusive term in the socialist lexicon against both book and man. Condemned, you could say, by bell, book and candle. But what received insufficient attention at the time, and which time has only confirmed the accuracy of, is Bloom’s remarkable analysis of Nietzsche and the crucial significance of the whole concept of values and validation. I would like to say just a few words on this which hopefully may contribute to a deeper appreciation of Bloom’s insights and the campaign to save our culture (and accepting, as I think we must, that all conflict is theological).

Bloom was the first to understand and to apply, in contemporary terms, the importance of what Nietzsche said on the subject of values. As we all know, Nietzsche proclaimed the death of God. However, Nietzsche was no triumphalist. He was, firstly, one of the greatest of all Greek scholars. He understood, at a profound level, the importance of belief in any, viable, culture. You simply had to have beliefs in something. If you didn’t believe in something, to paraphrase Chesterton, you ended up believing in anything because Nature abhors a vacuum. Crucially, reason was not a belief. It was an attribute or function of the mind and intellect. That, effectively, scuppered the Enlightenment which, anyway, had forgotten the importance of the insight of Hume:

“Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions.” (A Treatise of Human Nature)

Not ‘passions’, it must be added, in the sense of concupiscence, but, more, sentiment and desire, and with the proviso that the passions themselves are of a calm and mild nature. This was what Adam Smith called, ‘the great demi-god within the breast, the great judge and arbiter of conduct’ (The Theory of Moral Sentiments). These were ‘selfish’ interests in that all civilized people felt better, were better, when they were kind and generous towards others. This was what civilization was all about. It had little to do with altruism, being humble and lowering one’s sense of selfhood. It took an atheist, Hume, to recall us to the importance of belief.

With the French Revolution organized religion, and with it, the unitary sense of western culture, essentially, collapsed. Nietzsche, inhabiting the world of ancient Greeks, identified the unhooking of reason from belief as the culprit, then as now. A belief is a value. Man chooses values, what is good and what is bad, through an exercise of the will. The problem is we can choose ‘bad’ goods just as easily as we chose ‘good’ goods. The ancient world had always discussed the good life in terms of the knowledge and the virtues appropriate to it. To make good choices you first need to know what is right. This was where, Nietzsche said, something had gone terribly wrong. Because religion had declined, man had elevated reason in its place but the deep lessons of the Enlightenment, that belief is irreplaceable, had not been absorbed. Instead, man had pursued ‘material’ and empirical conceptions about nature and earthly Utopias that reduced human beings to automata. (William F. Buckley Jr. amusingly referred to this as a process to ‘immanentize the eschaton’). A huge and terrifying revolution now gathered pace. Darwin and, even more devastatingly, Marx enthroned materialism as the only religion for the ‘new’ man and woman (or should that be person?). Everything else was old hat, trash.

Marx professed to have discovered the ‘scientific’ laws of human development and triumphantly declared that these were material and dialectic. Man’s consciousness, the super-structure of belief, was a product of, and determined by, the structure of the mode of production of any given society. Being determined consciousness. Who you were in the capitalist pecking order determined what you were, your beliefs and values, your selfhood. Revolution would right all wrongs and usher in the communist society where we would all be free to do just what we liked when we liked. Anything goes. Here was a new religion. A religion of man. Philosophy joyously embraced the new creed. What was now important was not to understand anything. All that mattered was to change it.

True, the revolution, when it came, did not occur in the decadent west but in the peasant societies of Russia and China. Then, the workers had horribly succumbed to nationalism in two world wars and had actually fought one another. After 1945, conditions had even improved, the workers were better off materially than they had ever been. This was a huge source of anguish for the Left. Had Marx been wrong? The Frankfurt School re-examined the propositions of Marx in the light of recent history (it is, perhaps, significant that the Frankfurt School thought there was something worth saving). Marcuse, in particular, noticed something astonishing (Eros and Civilization,1955).

Part II to follow as I was unable to post a long article in one go.

Comment

-

Closing of the Western Mind, part II

Closing of the Western Mind, Part II .

Freud, who, of course, was unknown to Marx, proclaimed that he had discovered a phenomenon he called the subconscious. Like an iceberg where nine-tenths projects below the surface, we are all secretly guided, he said, for good or ill, by the deep and huge reservoir of our inner feelings, impulses, desires but which we dare not acknowledge. Marx had said that corrupt capitalist society had contaminated man. In a clever insight Marcuse proposed a ‘marriage’ of Marx and Freud. Why could Freud’s ‘discovery’ not be hitched up to classical Marxism? Then, the theory of the subconscious could be applied to every area of our (capitalist) life. What if even, or more especially, our subconscious, our whole personality, has been corrupted by capitalism to such an extent that we all now stand in need of liberation? Bloom saw that this was the revolution to end all revolutions, the end-point of the gloomy prognostications of Nietzsche. The whole notion of values, so important for the maintenance of anything that resembles civilized society, was detonated by Marcuse’s critique. Marcuse saw things in Marx and Freud that no one else had seen. Bloom saw things in Marcuse that no-one else saw or perhaps wanted to see.

The human subconscious, at its deepest level, requires liberation. This was the clarion blast of Marcuse. So, any behaviour is permissible. Violence is simply the cry of the oppressed. Drugs can help in the process of finding oneself (how Aldous Huxley must, one trusts, have regretted his early experiments if he could have lived to see the result). Promiscuity is mandatory. Abolish the family. Father’s only half-abuse their daughters, they can be more thoroughly abused by the State. Western civilization was based on ‘psychical’ oppression. Overthrow the oppressors. Here is an endless revolution, a revolution for the ages. And it avoids all of those problematic changes to the institutions that had so bedevilled Marxist thinking. Who cares about Congress, parliaments, the courts? Here is the new Marxist man and woman who has been purged from the inside. Institutions can even play a useful role in the revolution. Stuff them full of Marxist appointees, require then to promulgate socialist ideology, then we have a ‘virtuous’ cycle of propaganda which radicalizes the masses who, in turn, incite further change. The old sign posts will remain in place. But the commissariat will ensure they point nowhere, give misleading information, in a world inhabited by the new Marxist creation. Like the lost hikers on the mountain top who shout ‘We are here,’ the whole world will be filled to the uttermost with meaningless statements (texting, anyone?).

The greatness of Bloom’s book, if it only stopped there, would have ensured its place in the fast vanishing canon of great books of the west (Bloom has some wise words on the whole notion of the canon of great western books). But Bloom’s work is no mere exercise in horripilation. He provides a wonderful and hopeful corrective to the bottomless mendacity of the Left. Bloom explained that Marcuse was mistaken, dreadfully mistaken, because he had not understood another important German thinker, Max Weber. For Weber, like Nietzsche, had identified values to be key to any society. There must be a notion of right and wrong. Weber saw the rise of Capitalism, which filled Marx with such loathing, as the triumph of what he called the ‘protestant ethic.’ A particular group of Christians applying the four cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude (each of which has a significant emotional component) had changed the face of the earth. Marcuse simply thought Weber was condemning religion, in the same (wrong) way Marxists thought Nietzsche had. But Weber was making a very profound point. Weber was referring to the ascendancy of spirit over matter. Man creates his culture. In every important respect, men and women are free. This is nothing less than a huge, devastating rebuttal of Marxism. More complete than the collapse of the Berlin Wall, which we now see had been merely the fall of bricks and mortar.

Ethics are the key to the de-marxification and de-toxification of our society.

The question we have to consider was put by Socrates.

‘If virtue is knowledge, will

Comment

-

I keep forgetting about this section of the forum!Originally posted by Peter View PostJust finished 'Hide and seek' by Stephen Walker - the remarkable true story of the Irish priest Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty who helped save allied soldiers and Jews whilst based at the vatican in WWII. The film 'Scarlet and the Black' (with Gregory Peck) also tells this story.

Regarding Hugh O'Flaherty, he lived in my home town from a very early age and there is a dynamic statue (in a walking pose) of this extraordinary man in the town centre.

http://www.radiokerry.ie/wp-content/...-Killarney.jpg

Comment

-

I've just given the book away to a friend, so I don't have the correct bibliography, but it was a book about the Stalingrad battle launched by madman Hitler that went seriously awry. All I can say is that if Hitler and his cohorts had not meddled in the affairs of professional soldiers, the German army may well have routed Stalin.

Anyway, the part that really got to me was the lack of logistical support (food and warm clothing) provided by the lunatics back in Berlin. A curse on their houses! Such freezing temeratures! How can any army fight in those conditions!Last edited by Quijote; 12-12-2014, 03:37 PM.

Comment

-

Yes and Napoleon had already been there and paid the price!Originally posted by Quijote View PostI've just given the book away to a friend, so I don't have the correct bibliography, but it was a book about the Stalingrad battle launched by madman Hitler that went seriously awry. All I can say is that if Hitler and his cohorts had not meddled in the affairs of professional soldiers, the German army may well have routed Stalin.

Anyway, the part that really got to me was the lack of logistical support (food and warm clothing) provided by the lunatics back in Berlin. A curse on their houses! Such freezing temeratures! How can any army fight in those conditions!'Man know thyself'

Comment

-

I own a lengthy, informative and enjoyable book on the Battle of Stalingrad. Or I thought I did. I searched for it after reading your post. It's no longer on my library shelves. No idea what became of it. I must have loaned it to someone many years ago and totally forgot to reclaim it. Come to think on it, I don't believe I've read the book since the mid or late 1970s. Yes, we're fortunate that, in the end, Hitler proved incompetent. The shame is that his failings did not manifest themselves sooner.Originally posted by Quijote View PostI've just given the book away to a friend, so I don't have the correct bibliography, but it was a book about the Stalingrad battle launched by madman Hitler that went seriously awry. All I can say is that if Hitler and his cohorts had not meddled in the affairs of professional soldiers, the German army may well have routed Stalin.

Anyway, the part that really got to me was the lack of logistical support (food and warm clothing) provided by the lunatics back in Berlin. A curse on their houses! Such freezing temeratures! How can any army fight in those conditions!

As for me, I decided to postpone "The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason" and relax with a fantasy novel be Elizabeth Moon.

Comment

-

I intended to write a summary of reading highlights and lowlights from 2014 and post it here early January. Me being me it slipped my mind...until now.

I read thirty-seven novel length books last year. Seven, including two unsolicited loans from my brother, were first reads. The rest were rereads. The majority were fantasies. Six related to some aspect of classical music. Four were histories from the American Civil War era. The two loans concerned "pro" wrestling, a field I would not on my own single out for in-depth study. (That said, I found one of the two well written, informative and enjoyable. The other was fluff, but an easy read.)

HIGHLIGHTS:

- Award for the most read books of 2014 goes to David Eddings' "Belgariad" and "Malloreon" series, individual titles having received their eighth or ninth readings. Honorable mention goes to Stephan Donaldson's first two Thomas Covenant Chronicles, individual volumes getting seventh or eighth readings.

- Award for most disappointing reads of 2014 goes to Stephan Donaldson's "The Last Chronicles of Thomas Covenant". Much as I consider the first two sets of Chronicles some of the best modern fantasy ever published, so do I consider the much later written "Last Chronicles" a dismal failure.

- Award for best rereads of 2014 goes to Stephan Donaldson's first and second "Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever". These are the books that turned me on to the possibilities of the fantasy genre during the 1980s. I've maintained a special love for them ever since.

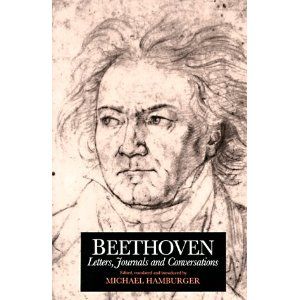

- Award for best new read of 2014 goes to Jan Swafford's newly published "Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph".

- Award for best read of 2014: "Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph".

Thus far this year (2015) I have read:- Elizabeth Moon's "Limits of Power". (fantasy)

- Robert Harris' "Pompeii". (historical fiction)

- Brandon Sanderson's "The Way of Kings". (fantasy)

I currently read "Words of Radiance", follow up to Way of Kings. At around 1000 pages each, these Sanderson titles are quite a time sink for a slow reader like me.

Comment

Comment